Digital vs. Analog Broadcasting: Whose Spectrum Is It Anyway?

12 Mar 2013 Charles Choi

Preface

Hello! This is my follow-up post to Digital vs. Analog Radio Broadcasting: A Slightly Apocryphal Explanation. If you haven't done so, I highly recommend you read it first before going forward, as I've made technical simplifications for lay readers.

My aim is to survey what I think are the most immediate logistical and public policy issues that surround Internet (aka Online) radio broadcasting. It is by no means comprehensive but intended to start informed conversation on the matter.

Disclaimers and Clarifications

- This post will concentrate on the mechanics of radio broadcasting in the United States. It will not, however, cover content concerns such as artist's rights and royalties, which is another discussion all on its own.

- I am not a lawyer and am not conversant in FCC law.

- I have worked in college/community radio (WTJU 91.1FM) as both an announcer (10 years) and an administrator (President, 2 years).

- I am computer engineer with over 20 years of experience in developing applications ranging from multi-tiered web services to embedded system design. At present I write mobile applications mostly for iOS (iPhone & iPad) and some Android.

Okay that out of the way, let's proceed.

The Ways to Digital

At current there are two incompatible ways for radio broadcasters to provide a direct [1] digital signal to listeners:

-

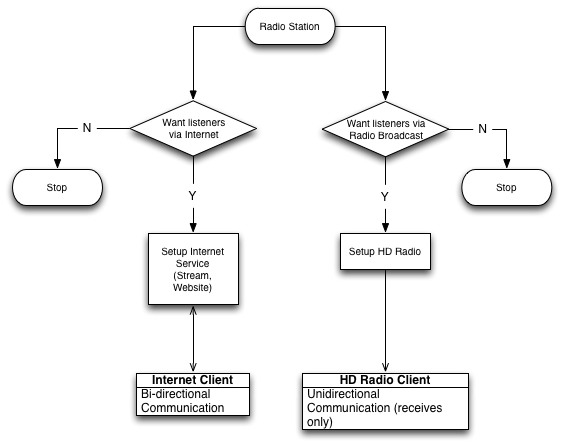

Digital audio broadcast, which in the United States is implemented using the HD Radio format. It relies on using radio wave broadcast as the physical layer and digital signaling as the logical layer. It requires receivers that are designed to process the digital signals it receives and convert them to analog for audio playback. It is unidirectional and the receivers must be within range of the broadcast tower to work.

-

Internet stream and/or download provided by digitizing the audio stream and transporting it via TCP/IP. This is referred to as Internet or Online radio. Any Internet capable device (or client) that is capable of converting the digitized stream back to analog can be considered a receiver. This same client can potentially send information back to the source of the stream (or download), as Internet communication can be bi-directional.

The figure below shows a simple decision tree for a radio station as to what kind of digital signal to provide.

Why Bother Going Online?

The great opportunity for radio stations with Internet broadcasting is bi-directional communication with listeners. With bi-directional communication, the following things become possible:

- Analytics - Direct and precise measurement of audience behavior at the granularity of an individual listener.

- Engagement - The experience provided can be tailored to the desires of the listener.

- Geographic Reach - The range from which listeners can listen is not bound by radio wave broadcast.

All of the above can be translated into monetizable transactions. This observation has not gone unnoticed by commercial enterprises.

HD Radio Is Not Online Radio

By virtue of being tied to a broadcast tower, HD Radio in contrast cannot offer analytics, engagement, nor the geographic reach that Online radio can offer. HD Radio does, however, offer greater efficiency in broadcast than Online radio in the same way that analog broadcast does by transmitting a signal over the receiving area. In short, the opportunities for monetization with HD Radio are far less than what Online radio can offer. It's an understatement to say that market penetration of HD Radio receivers is far less than that of AM/FM receivers. Consequently, I'll focus the rest of this post on Online radio.

"Skate to where the puck is going"

In 2013, the dominance of TCP/IP is evident in the proliferation of Internet capable devices available in the market today. A subset of such devices include: computers (desktop and notebook), tablets, mobile phones, TV sets, set-top boxes, DVRs, network attached storage, and digital cameras. From a radio broadcaster's perspective, the technology used to distribute digital content is directly tied to the number of devices that are capable of processing that content. Internet capable devices have considerable market advantage over unidirectional devices because there are more of them around, leading to more opportunities for monetization. This observation is central to formulating public policy, so much so that it merits a brief discussion of the market economics behind broadcasting, so we can return to this point later.

Whose Spectrum Is It Anyway?

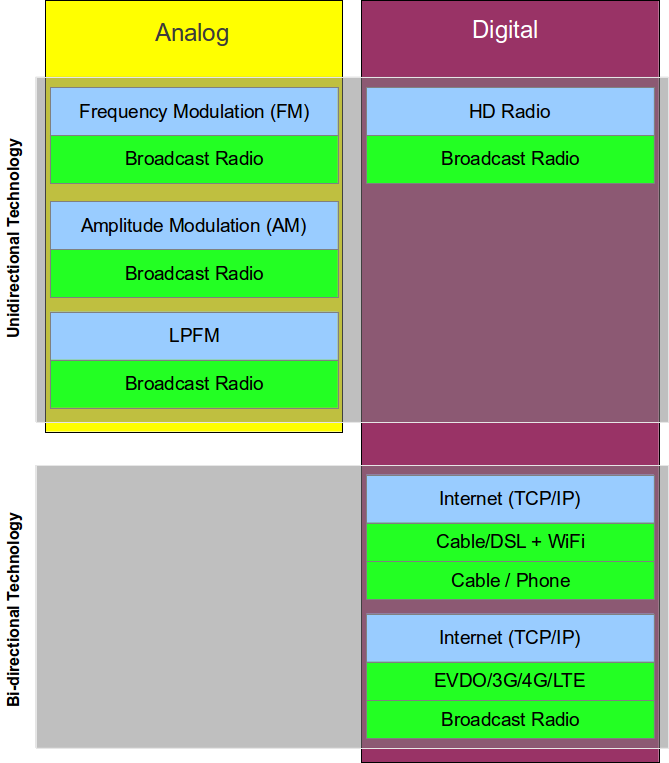

Let's return to the radio technology stack diagram from my prior post:

Note that for all the stacks, access to the physical (green) layers is regulated by a combination of Federal, state, and local governance. In particular, radio frequency (RF) spectrum for broadcast is controlled by the FCC. The underlying legal logic is that the RF spectrum is a public good which cannot be owned. However RF spectrum can be licensed, and so a variety of mechanisms have been devised to mediate access to it by commercial and non-commercial broadcasters.

For radio broadcast, listeners could simply buy a device which supported their logical layer of choice (typically AM/FM) and access the physical layer of radio broadcast for free.

This changed with the Internet.

In the United States, privately-owned phone, cable, and mobile wireless technology vendors negotiated RF spectrum licenses as well as land rights and other public goods to build TCP/IP networks (aka the Internet) whose access was through the commercial market. Most Internet users must now pay for physical layer access either through their cable/DSL provider or through their mobile telco (phone) provider. In many cases users do both.

The popularity and utility of Internet access has grown in the United States to the point where the argument that all citizens must have Internet access is gaining currency. Therein lies a problematic public policy issue because today most access to the Internet is controlled by private vendors. Thinking about Internet radio in cars is a good place to examine this issue.

"A Cold, Harsh Reality for Radio" (back to our puck)

In A Cold, Harsh Reality For Radio [2] by Eric Rhoads, he had this choice quote from a panelist at a conference he attended:

- "AM and FM are being eliminated from the dash of two car companies within two years and will be eliminated from the dash of all cars within five years."

A statement like this triggers a negative reflexive reaction from radio broadcasters because it challenges a dominant (if not primary) means for listeners to get access to them. More bluntly, it attacks the business model for radio. While it's debatable whether or not that schedule is true, what I find undeniable are the market forces enabled by Internet access that wants it to be true.

The state of Internet car radio circa 2013.

From the perspective of the auto industry, computers are being used to differentiate and extract efficiencies for competitive advantage at an aggressive pace. It's been estimated that "more than 80 percent of car innovations come from computer systems and that software has become the major contributor of value (as well as sticker price) in cars."

The auto industry faces a number of pressures old and new:

- Globalized competition which encourages commoditized pricing.

- Demographic shifts where 18-to-34 year old buyers of automobiles are declining or put another way: "Gen Y aren't buying cars."

Auto manufacturers face extreme market pressure to remove or replace any feature for increased profit. AM/FM radio viewed in this light is a sunk cost compared to the monetization opportunities for built-in Internet car radio, even if the audience size for Internet radio is smaller.

Potential ways auto manufacturers can make money from Internet car radio that they cannot from AM/FM include:

- Revenue share for sales of analytics data

- Revenue share for purchases of digital media

- Partnering with mobile telcos for Internet data plans

Back to Public Policy

Because frequency spectrum has economic value and is allocated by the government, how it gets allocated and regulated is a public policy matter. The usage of that spectrum is determined by what people want to do with it. For many people, this means using it for Internet communication.

There are broad opinions on this, ranging from laissez-faire to socialist arguments for how to allocate frequency spectrum. I think we are best served with flexible policy that reflects how people adopt and phase-out their use of technology over time. Private ventures can and do innovate to bring new technology to society via market incentives and are often rewarded with monopoly control in return for the social good the technology offers. But if the technology starts to resemble a public good then it is natural for the public to challenge the economic control of it and this can often serve private ventures.

Automobile manufacturers are under no regulation to put AM/FM radios in cars sold in the United States. There is an argument that they should, stemming from a public safety concern: They support the Emergency Alert System.

The Emergency Alert System(EAS) (the system which now supercedes the Emergency Broadcast System) is a national warning system in the United States primarily used for local weather emergencies. The case for continued support for AM/FM broadcast because it supports EAS is a pragmatic one: it exists, works, and is accessible due to the huge legacy base of receivers.

A counter-argument to this is that listener behavior is changing to due Internet usage, accelerated by commercial interests with a vested interest in seeing higher Internet usage for monetization opportunities. Following this argument, AM/FM broadcast will eventually become a vestigial technology, one to be obsoleted and whose frequency allocation is to be re-evaluated. Continuing this argument, there would exist a need to extend EAS to support where the users are: the Internet.

Some policy questions to ask then are:

- Should AM/FM broadcast be considered essential to EAS to live in perpetuity?

- Should AM/FM broadcast be deprecated? If so, how, and what should take its place including a migration path for EAS? If not, then what is the opportunity cost for keeping status quo?

- Should Internet access be considered a public good? If so, how?

Summary & Closing Thoughts

Economic motivation is central to telecommunications policy. It is why people fight over such policy so strongly: access and control of the resources (RF spectrum, land rights, etc.) covered by telecommunications policy can confer great monetary reward. The level of access and control for Internet communications is still nascent because its technical development has outpaced public discussion on how it should be used. As a consequence, the private interests in the United States that have developed Internet infrastructure hold control of its access. It is open to discussion whether this is desirable as that access is built on top of public goods allocated by Federal, state, and local governance.

Thanks for reading this far. I hope that this and my prior post can help spur informed discussion on public telecommunications policy especially with regards to Internet access. I invite you to read more on this topic to form and share your own opinions on Internet access - we are all in this together!

[1] Direct meaning non-relayed. For example, cable TV redistribution would be a relayed broadcast, so we don't cover that case here.

[2] Thanks to Nathan Moore, Station Manager for WTJU 91.1FM for sharing this article.

Thanks to Elizabeth Hull for proofing this post!