Unleashing the Editing Superpower of Emacs

29 Jul 2025 Charles Choi

This is a contribution to the Emacs Carnival 2025-07: Writing Experience collection of posts on Greg Newman’s blog.

Emacs boosters often extol its virtues in editing text. But what does that really mean? In this post I’ll scrutinize that assertion. Hopefully by the end of this post, you’ll understand why long-time Emacs users so celebrate editing in it.

Any text editor worth its salt will let you type text into a file, save it, and subsequently edit it. The table stakes are to reliably transcribe thought into characters, typically one at a time. If that is all one wants, there really is no distinction in using Emacs over another editor.

Thoughts however do have organization and context. Editors like Emacs take advantage of this by providing features that exploit structure. The benefit for doing this is letting users work less in transcribing their thoughts to digital form.

For example, in prose, characters are grouped as words, words grouped as sentences, sentences as paragraphs. Emacs offers dedicated commands to manipulate such text structures. Implicit is the notion that Emacs is able to identify different structures in text. As text structure becomes more elaborate, richer commands can be made to edit them.

Working less to capture your thoughts is the core motivation for using Emacs.

When text is organized into different structures (character, word, sentence, paragraph, balanced expression), different commands can be defined to act on them. Emacs supports the following built-in actions for editing prose:

- Marking

- Copying

- Killing (Cutting)

- Transposing

- Transforming (upper/lower case, capitalize )

- Navigation ( previous, next, forward, backward)

A quick inventory shows no less than 50 commands available to edit text structures given the above. And that is just the tip of the iceberg. Support for pairing braces and quotes, templates, selection based on structure, abbreviation, completion, indentation, and navigation/movement all work in concert to help the writer to work less in achieving their end.

With all this bounty, there’s a catch. Discovering and knowing all these commands (much less their bindings) has a profoundly steep learning curve. For those few who climb it, my hat-tip to you. For the great mass of others (myself included), they forego using such commands either due to lack of awareness or because they were too cumbersome to recall. Invariably when faced with failing to recall that magic command, one ends up laboriously editing to achieve the desired result, rationalizing that it would be faster than the cost of lookup, disrupting whatever flow state they had at the time.

This is a user interface problem.

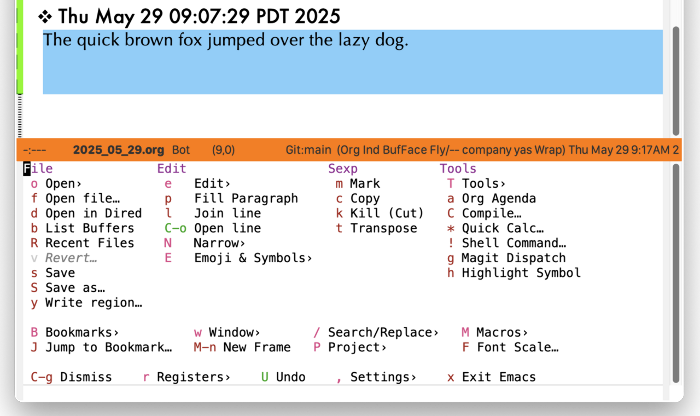

My work on Casual has been a personal effort to address the usability of accessing so many commands by applying an information architecture to a hierarchy of keyboard-driven menus. Within Casual, there is a set of menus focused on editing which I call EditKit whose top level menu is shown below:

From this menu, I’ve aggregated many commands that I’ve encountered (TIL) over my decades of using Emacs. Within this menu tree, I’ve captured commands for editing text structures, registers, and rectangles which have frustrated me in the past due to my failure to recall them.

For a look into what commands are offered in the “(e) Edit›” menu, take a deep read of this link. In particular it incorporates the ability to moving text as described in my earlier post “Moving Text Elegantly in Emacs”.

The Emacs Writing Experience and Closing Thoughts

As Emacs was designed to be extensible early on, we now have over three decades of collective work in features to support editing different text structures, all with the goal of improved efficiency. Emacs users are fortunate to have access to them as many of these features are not found in other editors. In this regard, Emacs can be seen as an “unfair” advantage.

The cumulative effect of having access to such a bounty is the net effect of letting the writer devote more time to thinking instead of mechanically wrangling characters on a screen. In using Casual, I have found such access. That said, other users might prefer a different interface. Regardless, the commands doing the work remain the same. If you can use them, you can work less to get what you want done.

Isn’t that why you wanted to use Emacs in the first place?

Links

Some links to packages and features that I’ve found useful for my Emacs writing experience.

- abo-abo/avy: Jump to things in Emacs tree-style and my Casual interface for it kickingvegas/casual-avy: Casual Avy - An opinionated Transient menu for Avy.

- Matching (GNU Emacs Manual) (aka Electric Pair Mode)

- joaotavora/yasnippet: A template system for Emacs

- Abbrevs (GNU Emacs Manual)

- Hippie Expand (Features for Automatic Typing)

P.S.

It's not lost on me how close this topic touches on both input method editors (IMEs) and LLMs as a means of capturing thought. They are both broad topics which I can not adequately cover in this post. That said, much of my thinking along these lines are informed by this presentation by Thomas S. Mullaney on his book The Chinese Computer - A Global History of the Information Age at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California. The upshot is that for everybody, "writing" using computers is evolving into a form where direct transcription is the exception and not the rule.