Thoughts on Funding Free Software Development

13 Nov 2025 Charles Choi

“I have always depended on the kindness of strangers.” — Blanche Dubois from “A Streetcar Named Desire”, Tennessee Williams.

DISCLAIMER: None of this post should be considered as financial or career advice of any kind. All views and opinions expressed here belong solely to Charles Y. Choi.

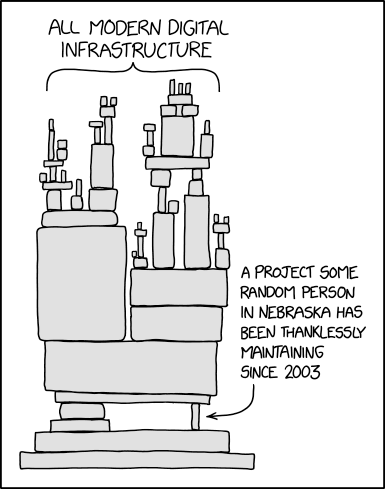

Not getting paid for making free software has long been recognized as a conundrum in the early 21st century, where much of its discourse is trenchantly summarized by the xkcd drawing “Dependency” [1] shown below.

For some time I’ve been gathering my thoughts on this matter, with stances that I’ll share in this post today.

Fundamentals on Bringing a Product to Market

Before talking about software, let’s review the basic steps needed to bring a physical product to market.

-

Design & Development

In this step, the intellectual construction of the product is defined.

-

Manufacture

In this step the product is mass produced. This step must occur after step 1.

-

Distribution

In this step the manufactured product is delivered. This step must occur after step 2.

-

Marketing

In this step, awareness of the product to its target market is raised to induce demand for it. Ideally this step is taken when there is high confidence in delivering the product to the market.

-

Support

In this step, the producers provide support for the product after it has shipped. This step must occur after step 3.

For a physical product, each step has a monetary cost associated with it. If the producer wishes to make a profit by selling the product, the price of the product must be greater than the cost to produce it. This leads to the incentive to manufacture and distribute as many copies as possible to maximize profit. At scale, the dominant costs are manufacturing and distribution for a physical product.

Software is Different

If the product is software using internet distribution, then its costs for manufacture and distribution become effectively zero. For a software provider, the dominant costs to bring a product to market are design & development, marketing, and support. Such costs are largely fixed with respect to demand. Since software has no intrinsic manufacturing nor distribution cost, for-profit software must resort to creating artificial scarcity to justify (and protect) profit that scales with meeting demand. Tactics to create scarcity include:

- Constraining code to be closed-source.

- Distributing only executables, typically code-signed to a model of computer.

- Compilation-enforced licensing, typically tied to a subscription model.

What about Free Software?

With that background in place, let’s talk about free (both in speech and beer) software. In this post, I make no distinction between free (libre) and open source licensed software [2] as their differences fixate on the user’s ability to modify and redistribute received software. In contrast, this post views free software through the lens of the costs required to deliver said software to the market as described above.

Free software requires that its distribution be zero-cost to users. In contrast with for-profit software, free software evades the creation of artificial scarcity. In light of this, what options are available for developers who want to get paid for making free software? Here are three:

- Ask users to voluntarily give money after the software has been produced.

- Attach the developed software to a service or hardware-based business model.

- Get money upfront from users (or organizations) who have an interest in realizing some specific software, before its design and development are completed.

The first option offers providers no financial incentive to make free software, nor offers a reliable path to cover the cost to make it.

The second option relies on indirect compensation where the service or hardware revenue is expected to cover the cost of software development. Scarcity is imposed by restricting access to the service or hardware based on payment. This option is often taken by startups funded with venture capital.

The third option offers direct financial incentive for the developer to create free software, as money is taken by the developer with the expectation that said software is delivered at a future date. With this option, the design & development step is what is considered scarce. Upfront funding can come in a variety of forms, but largely fall into the following patterns:

- Institutional funding, where an organization puts up the funding.

- Angel funding, where a small group (< 5) of people contribute the funding.

- Crowdfunding, where a pool of small contributions from individuals (> 1,000) is gathered, typically with a target funding goal.

Which approach is taken can vary widely depending on the functionality of the software and the relationship (or lack thereof) between the developer and their benefactors. Note that getting money upfront to develop software precludes gaining profit from it based on demand after it is made, as free software insists its distribution be zero-cost to users. The only avenue for developer profit in this case is to demand funding that exceeds the baseline cost of producing the software.

Getting money upfront implies negotiation, which gives the developer agency to choose whether to commit to building the desired software. It also significantly raises risk to all involved parties if the software fails to be built.

Upfront funding aligns the incentives for producers and consumers of software by having agreement on a future deliverable:

- Consumers pay to get the future software deliverable.

- Producers work to build the future software deliverable.

While the exact number is unknown, I think a safe presumption is that single developers have built the vast majority of free software packages as evidenced by the Linux, Emacs, Python, and Node ecosystems. Most all of them resort to appeals to user gratuity, which is not enough to actually cover the market cost of designing & developing that software.

Given the above options for upfront funding, I’ll further make the assumption that most single developers do not have access to institutional nor angel funding. So, let's talk about crowdfunding.

Crowdfunding

The dominant cost to producing software is labor. A common project scope is a three month schedule with a single developer. Estimating a market rate salary of $10K/month, this results in a budget of $30K to deliver software at cost.

Crowdfunding has proven to be successful in raising that level of funding, by mitigating risk to all participants by defining a funding goal. Typically a funding goal is set within a window of time. If the goal is not met, then patrons who already put money down will have their money returned and the producer is not committed to work on the software. With high demand, the goal can be met with potentially low financial risk to an individual patron. For example, if 30,000 people gave $1, the above budget could be met.

Reaching those 30,000 people is another thing altogether, as crowdfunding is an exercise in marketing.

To have a successful crowdfunding campaign, the producer must deliver a message about a future software product that is compelling enough to create demand for it. Common tasks undertaken to make a crowdfunding campaign include producing:

- A video describing the envisioned product.

- Marketing copy for said envisioned product published on web, possibly print.

- Brand merchandise for patrons.

- Order taking

- Fulfillment

- Press campaign.

- Social media campaign.

Note that the success of the crowdfunding campaign will depend on how effective its message is to the target audience. Each audience is bespoke, meaning that not all things successful for one crowdfunding campaign can be applied to another. Invariably, the software producer must know their audience.

Single developers producing free software might look at the above and say “nope.” Most certainly it is a lot of work, much of which is perhaps outside the comfort level of persons whose focus has only been on coding. It is also not a common practice to use crowdfunding to support free (libre) or open source development. Regardless, if a developer wishes to be paid to work on free software, they will need to get comfortable with pitching their work beforehand to get the funding to do it. Wider-scale use of crowdfunding could bring better agency to the developer and enable the development of larger scope free software projects that would be untenable with volunteer time.

Observations and Closing Thoughts

This post has been a distillation of my thinking about free software and how it can be sustainably funded. From this exercise are some of my personal observations:

If you have a software idea that you want to distribute for free, determine as soon as possible if you want to get paid to make it.

If you don’t care about getting paid, ever, for that work, then GO MAKE IT! Be thankful for whatever gratuity you get from it.

If you do care about getting paid to make the idea, then explore what funding model fits best for the idea. At this point, DO NOT MAKE THE IDEA AND PUBLISH IT.

If you get funding, GO MAKE THE THING. MAKE PEOPLE HAPPY.

If you don’t get funding, let it rest. Move on to the next idea.

If you already produced free software that was built without funding, accept that you will never recover your development cost.

To reiterate, free software requires that its distribution be zero-cost to users. This is excellent for user freedom but comes at the expense of agency for developers: Users can not be compelled to pay developers for their already published work. Developers can however make new features and fixes contingent on funding. I think this position is fair and defensible for the obvious reason that software developers must pay for the costs of living in a material world.

If you’ve made to here, thanks for reading! Feel free to share your thoughts about this post on Mastodon or Reddit.